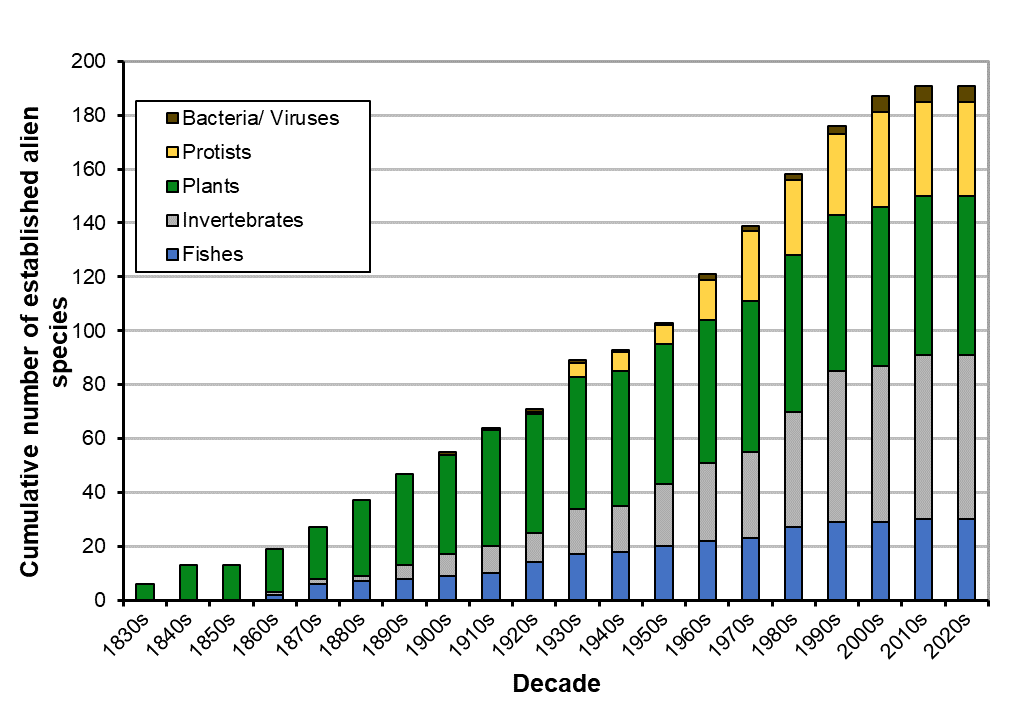

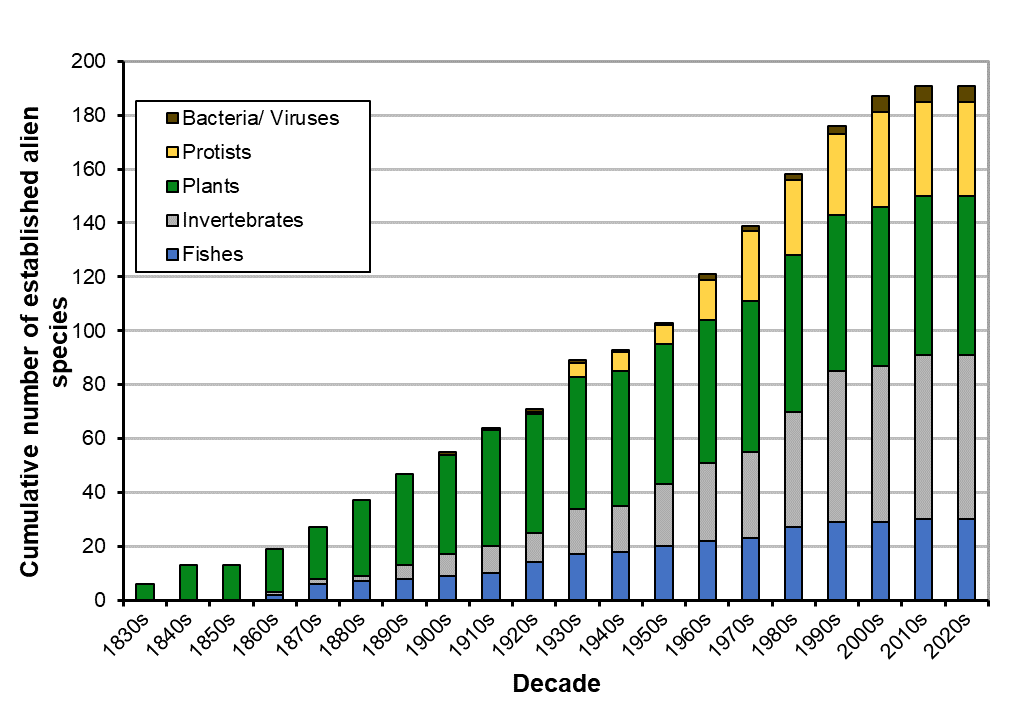

This indicator summarizes the cumulative number of aquatic alien species in the Great Lakes and the rate at which introductions have occurred. Figure 1. Cumulative number of established aquatic alien species, by taxonomic group, in the Great Lakes by decade (note: protists include algae, diatoms and protozoans; invertebrates include annelids, bryozoans, coelenterates, crustaceans, insects, mollusks and platyhelminthes).

Figure 1. Cumulative number of established aquatic alien species, by taxonomic group, in the Great Lakes by decade (note: protists include algae, diatoms and protozoans; invertebrates include annelids, bryozoans, coelenterates, crustaceans, insects, mollusks and platyhelminthes).

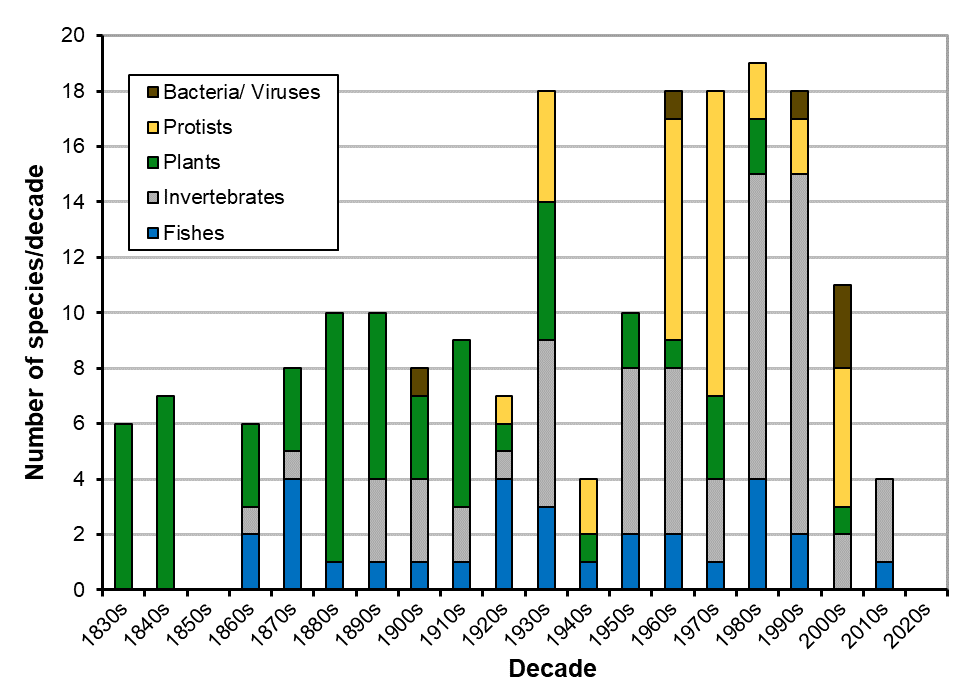

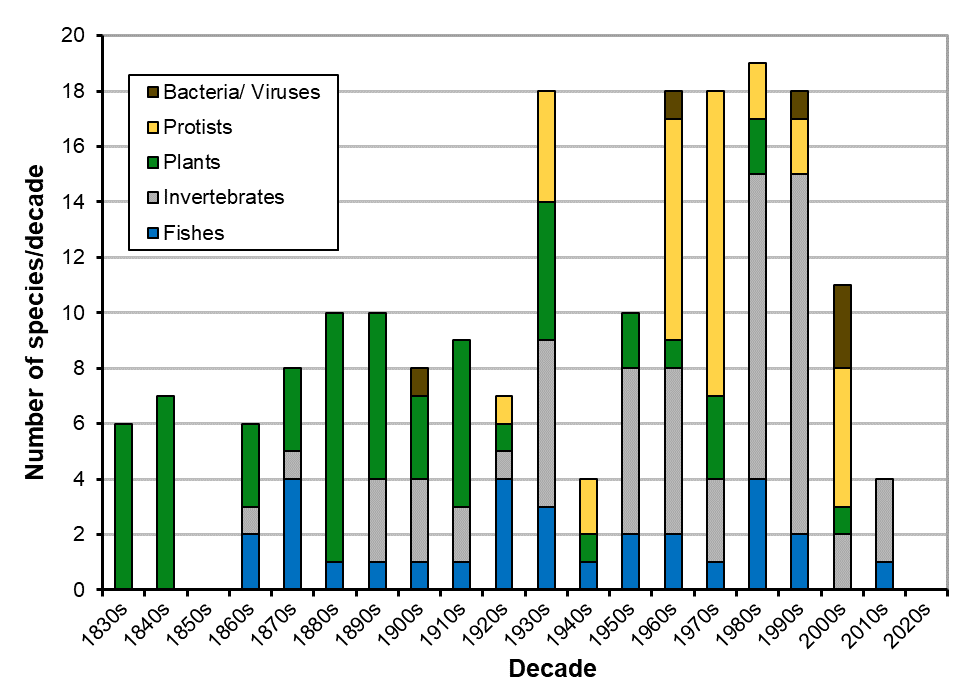

Figure 2. Number of established aquatic alien species, categorized by taxonomic group, discovered in the Great Lakes per decade.

Status:

- The number of aquatic alien species in the Great Lakes basin has steadily increased since the first species was documented in the 1830s. As of December 2020, 191 alien species were established.

- Between 1839 and 1950, an average of 8.5 new species were established per decade. Between 1950 and 1999, the average rate of new alien species establishment increased to nearly 17 species per decade. This increased rate of establishment coincides with the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959. The higher rate during this period may also be a result of increased detection efforts.

- The rate of newly established species appears to have declined dramatically in the current decade. Only four newly established alien species have been discovered in the Great Lakes since 2010. This includes three species of planktonic crustaceans and one species of fish—Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella ).

Although sterile (triploid) Grass Carp have been caught previously in the Great Lakes, diploid Grass Carp were first detected in the Great Lakes basin in 2011. Natural reproduction has recently been documented in the Sandusky River in Ohio. However, there is not yet anyevidence of an established population in Canadian waters, and surveillance continues (DFO 2019).

- The fact that only four new alien species have been established since 2010 may reflect increased awareness of invasive species issues, enhanced monitoring efforts and/or heightened prevention and control efforts, specifically, more comprehensive ballast water regulations introduced by Transport Canada in 2006.

The current list of nonindigenous species in the Great Lakes was downloaded from the Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System (GLANSIS – NOAA 2020). Species included are not native to any part of the Great Lakes basin but are established in the Great Lakes and connecting waters. The database includes information on the origin of species and the year that they were first collected. Species were grouped into five taxonomic categories (bacteria/viruses, protists, plants, invertebrates and fishes) and the cumulative number and number of invasions per decade were graphed (Figures 1, 2).

There are some important caveats with respect to the information used for this indicator: some species established in U.S. waters of the Great Lakes and not yet found in Ontario waters are included; species native to one part of the Great Lakes basin that have been introduced to a new part of the basin are not included; and potential alien species whose origins are not clearly known are not included. Additional alien species are likely present and have not yet been found or established. There has also been no overall assessment to determine which species have been harmful some, such as intentionally introduced Pacific Salmon species have had positive economic and social impacts. However, this database is the best available information and is a good indicator of the risk to Ontario’s biodiversity posed by alien species in the Great Lakes Ecozone.

• Access GLANSIS database

Web Links:

Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/res/Programs/glansis/glansis.html

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry – Invasive Species https://www.ontario.ca/environment-and-energy/how-government-combats-invasive-species#section-8

Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters – Invading Species Awareness Program http://www.invadingspecies.com/

Ontario Invasive Plant Council http://www.ontarioinvasiveplants.ca/

Invasive Species Centre http://www.invasivespeciescentre.ca

References:

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). 2019. Asian Carp. [Available at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/profiles-profils/asiancarp-carpeasiatique-eng.html

Mandrak, N. and B. Cudmore. 2010. The fall of native fishes and the rise of non-native fishes in the Great Lakes basin. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management 13(3): 255-268

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.

Mills, E.L., J.H. Leach, J.T. Carlton and C.L. Secor. 1993. Exotic species in the Great Lakes; a history of biotic crises and anthropogenic introductions. Journal of Great Lakes Research 19:1-54.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2014. Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System. [Available at: http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/res/Programs/glansis/glansis.html (Accessed June 20, 2017)]

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). 2012. Ontario invasive species strategic plan. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Peterborough, ON.

Ricciardi, A. 2006. Patterns of invasion in the Laurentian Great Lakes in relation to changes in vector activity. Diversity and Distributions 12:425-433.

Invasive plants are an immediate and growing threat to Ontario’s biodiversity, economy and society. They spread aggressively, choking out native vegetation, threatening our natural areas, and the species that depend on them. They can also degrade agricultural lands, and impact forest regeneration, costing Ontarians millions of dollars annually in control costs and lost productivity. Invasive Phragmites or European Common Reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis) has been described as Canada…

Read More

Figure 1. Cumulative number of established aquatic alien species, by taxonomic group, in the Great Lakes by decade (note: protists include algae, diatoms and protozoans; invertebrates include annelids, bryozoans, coelenterates, crustaceans, insects, mollusks and platyhelminthes).

Figure 1. Cumulative number of established aquatic alien species, by taxonomic group, in the Great Lakes by decade (note: protists include algae, diatoms and protozoans; invertebrates include annelids, bryozoans, coelenterates, crustaceans, insects, mollusks and platyhelminthes).