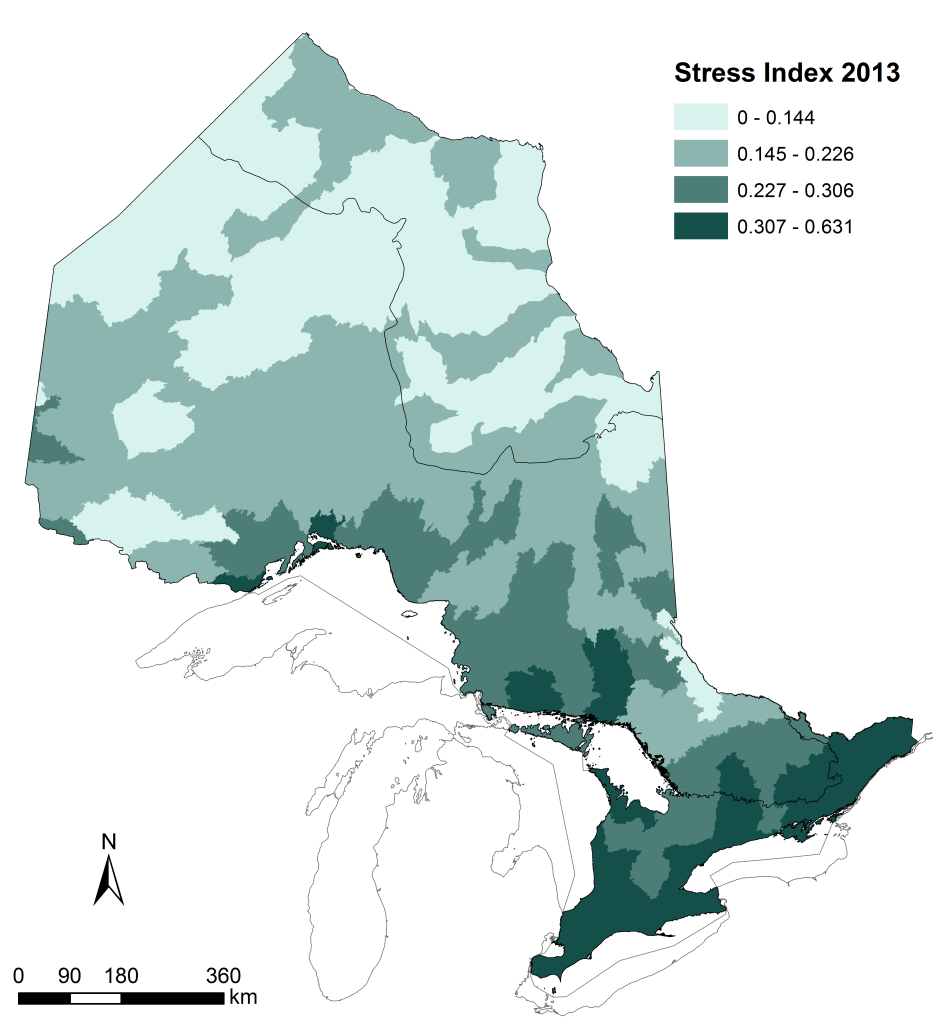

This indicator uses the Aquatic Stress Index from Chu et al. (2003, 2014) to represent the relative intensity and distribution of threats affecting aquatic habitats in Ontario. The Stress Index was developed to identify the intensity of human stressors for each tertiary watershed across Canada and incorporates information on population density, roads, industrial activity, agriculture and forestry.

A) B)

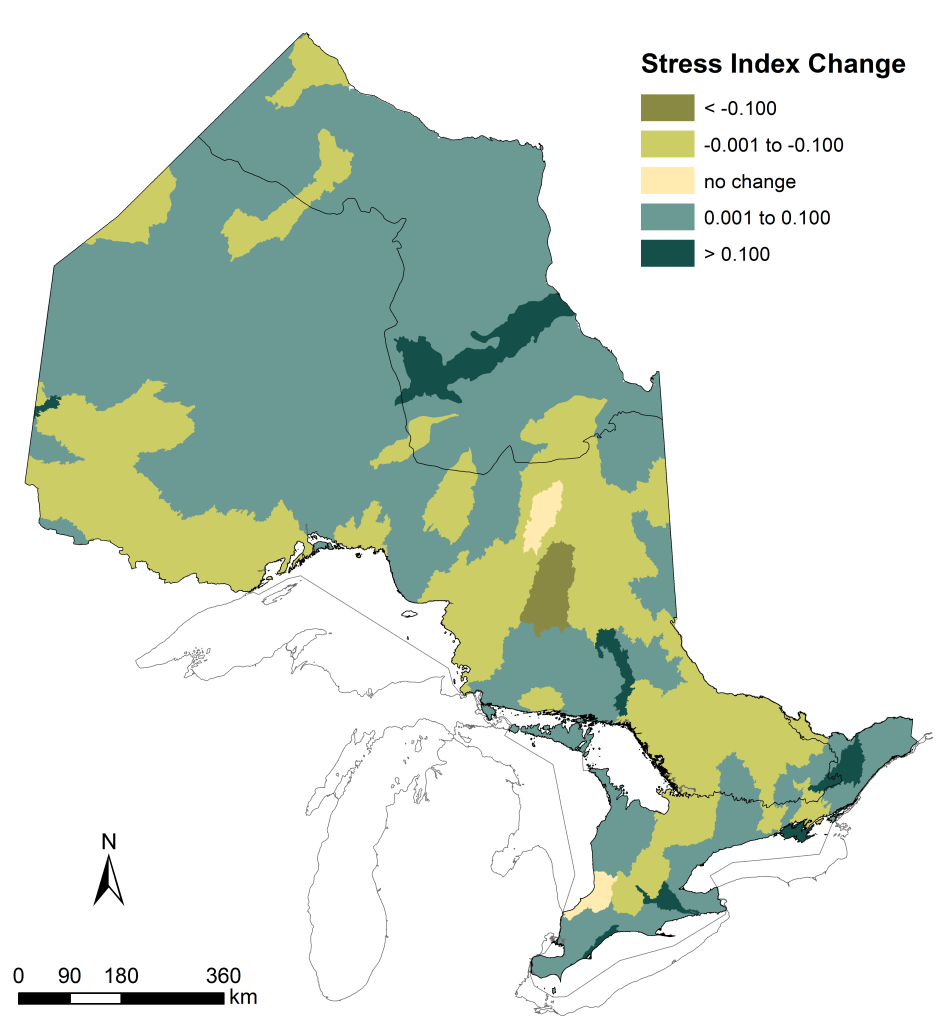

Figure 1. A) 2013 Stress Index for tertiary watersheds in Ontario based on Chu et al. (2015). Higher Stress Index scores represent a higher level of stress to aquatic ecosystems; B) Changes in Stress Index scores between 2003 and 2013 (negative values indicate reduced stress; positive values indicate increased stress).

Status:

- The average Stress Index for Ontario tertiary watersheds increased by 0.018 between 2003 and 2013, representing a 7.5% increase. The Stress Index increased for 90 watersheds (62%) and decreased for 53 watersheds (37%).

- Watersheds in the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone have the highest Stress Index values, suggesting that aquatic habitat loss and degradation is highest in this part of the province. The Stress Index has increased in 73% of watersheds in this ecozone since 2003.

- Watersheds in the southern part of the Ontario Shield Ecozone have high Stress Index values as do watersheds near population centres elsewhere within the ecozone. The northwestern portion of the ecozone has low Stress Index values. The Stress Index has increased in just over half (54%) of these watersheds since 2013.

- Watersheds in the Hudson Bay Lowlands Ecozone have comparatively low Stress Index values, however the Stress Index in most of these watersheds (76%) has increased since 2003.

Aquatic Stress Index values for this indicator are from the work of Chu et al. (2003, 2015). They estimated the stress placed on each watershed based on the distribution of stressors using census and business pattern data from Statistics Canada. Crop agriculture density, waste facilities, petroleum manufacturing, forestry, dwellings, discharge sites, and roads were selected for further analysis from a list of potential stressors. Values for the density of these stressors in each watershed were standardized by dividing each value by the maximum value across all watersheds. An overall watershed Stress Index was calculated (on a scale of 0-1) as the average of all the agricultural, industrial, and population stress values in each watershed.

Data for the 2003 Stress Index were from the 1996 Census and data for the 2013 Stress Index were from the 2006 Census. The change in the Stress Index between the two time periods was calculated as the simple difference between the 2013 and 2003 values for each watershed (Figure 1).

Related Target(s)

Web Links:

SOLEC 2011 [Watershed Stressor Index – p. 514] http://binational.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/sogl-2011-technical-report-en.pdf

Great Lakes Environmental Assessment and Mapping Project http://greatlakesmapping.org/

Great Lakes Aquatic Habitat Framework http://ifr.snre.umich.edu/projects/glahf/

References:

Chu, C., M.A. Koops, R.G. Randall, D. Kraus, and S.E. Doka. 2014. Linking the land and the lake: a fish habitat classification for the nearshore zone of Lake Ontario. Freshwater Science 33:1159–1173.

Chu C., C.K. Minns, and N.E. Mandrak. 2003. Comparative regional assessment of factors impacting freshwater fish biodiversity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 60:624–634.

Chu C., C.K. Minns, N.P. Lester, and N.E. Mandrak. 2015. An updated assessment of human activities, the environment, and freshwater fish biodiversity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 72:135-148.

Dextrase, A.J., and N.E. Mandrak. 2006. Impacts of alien invasive species on freshwater fauna at risk in Canada. Biological Invasions 8:13-24.

Helfman, G. 2007. Fish conservation: a guide to understanding and restoring global aquatic biodiversity and fishery resources. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Jelks, H.L., and fifteen co-authors. 2008. Conservation status of imperilled North American freshwater and diadromous Fishes. Fisheries 33:372-407.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.

Ontario’s 36 Conservation Authorities (CAs) are local management agencies that deliver services and programs to protect and manage water and other natural resources on a watershed basis. CAs work in partnership with all levels of government, landowners and other organizations. They promote an integrated approach and aim to balance human, environmental and economic needs. Strong and resilient natural ecosystems help humans adapt to many different challenges, including the impacts of climate cha…

Read More